The Story Teller's Apprentice

Seminar Paper

“We are young, and the fire flickers, glowing, warm on our

cheeks. Staring, fixated by the undulating pulse of embers,

images form and disappear, faces peer back blinking.

Patches of intense colour in the flame; the azure of deep

water, deeply polished metal, mirror. Patterns in the wood

jump suddenly as structures collapse, the burning wood

settles sending up a bevy of sparks towards a star filled

sky, the infinite inky blue black, cold as the deep.

You throw in a pebble -

Another - Boys always need to play with fire.

But we are warm, snug in fleece. And listen, father is

painting a story, older than us, old as time, illustrated

in the stars, illustrated with the shadows from his

gesturing hands moving across the trunks of trees behind.

And deeper in the wood are other shadows, real and

imagined. We are gripped by curiosity, even though we know

the tale as our own, but ever to hear it again, each twist

and turn, stirring the embers deep within, fear, longing,

love, loss; a wild, dangerous journey.”

Thoughts on story telling,

narrative, imagery, and shadows.

Walking the coast path at St Alban’s head I came across a

stone bench facing the sea, carved with the names and dates

of a couple. We all seek to leave a mark, to mark the

passing of time, to mark our passing through time. Below

their names there is a quote:

“ Time passes. Listen. Time

passes”

The quote is from Dylan Thomas’s play ‘Under Milk Wood’ (I

looked it up on my return)

and it continues:

“Come closer now.

Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets in the

slow deep salt and

silent black, bandaged night. Only you can see, in the

blinded bedrooms, the

combs and petticoats over the chairs, the jugs and basins,

the glasses of teeth,

Thou Shalt Not on the wall, and the yellowing

dickybird-watching pictures of the

dead. Only you can hear and see, behind the eyes of the

sleepers, the movements

and countries and mazes and colours and dismays and

rainbows and tunes and

wished and flight and fall and despairs and big seas of

their dreams.

From where you are, you can hear their dreams...”

I start this seminar paper with a paragraph of my own

creation, setting out some ideas that I plan to explore,

and include a quote from Dylan Thomas, master teller of

stories, realising though this rediscovery what an

influence he has been on me. An evocation of childhood

experiences. Combinations of words, some running together,

conjuring up pictures:

“bridesmaided by glow-worms down the aisles of the

organplaying wood. The boys are dreaming wicked of the

bucking ranches of the night and the jollyrodgered sea”

“ It is night neddying among the snuggeries of babies.”

Storytelling as art, the painting of images with words,

creating worlds in the imagination.

The following quote is a few lines from Italio Calvino’s

‘If on a winter’s night a traveller’:

“Long novels written today are perhaps a contradiction: the

dimension of time has been shattered, we cannot love or

think except in fragments of time each of which goes off

along its own trajectory and immediately disappears. We can

rediscover the continuity of time only in the novels of

that period when time no longer seemed stopped and did not

yet seem to have exploded, a period that lasted no more

than a hundred years.”

In context I am not sure to what Calvino refers

specifically, but this quote points to the likes of James

Joyce, Surrealism, automatic writing, word association, a

stream of consciousness, beatnik poetry, the likes of Jack

Kerouac, who typed on a roll of tracing paper so as not to

break the continuity of his writing with carriage returns.

For me it was a passion for the Lyrics of Dylan, with songs

like Shelter from the Storm and Hard Rain. each line of the

lyric conjuring up an image, a story told in glimpses.

Sometimes without need for a precise order.

Glimpses:

I was walking the dog in the early morning, before dawn,

thinking about this assignment. I could not help but look

through the lit windows of kitchens and bedrooms, a frisson

of excitement, my eyes drawn to the light, into other

lives; private spaces, framed by windows.

A photograph comes to mind, two photographs actually, that

together tell a story. One is a self portrait, the

photographer stands in a very public place, the middle of a

busy shopping centre, legs akimbo, looking straight at the

camera. Passers by pass by. The second photo shows the same

woman, but taken from a small camera on the ground. A

second look at the first photo reveals the camera lying on

the pavement between her legs. This camera has taken the

same moment in time, but the image is taken of a very

private space.

The allure of the blue flashing lights on the roadside that

might offer a glimpse of a traffic accident, The lure of

the screen, perhaps this has a root in these voyeuristic

tendencies. Eyes drawn to Cleavage or bulge; instinctive. A

television that is on in a room pulling the eyes like a

magnet, stronger even than the pull of the embers. The

window is in itself like a screen, framing a world within.

The framed space becomes another space, arousing curiosity,

needing exploration, offering a possibility of escape,

leading us into other worlds, worlds of imagination, of

dream, of collective memories.

I am interested in exploring the concept of this frame

through a fragmented narrative of image and word, in the

place were word meets image, where still image meets moving

image, where the time is represented between the frames, or

caught in short sequences of reciprocating animation. And I

am interested in a recent manifestation of this frame; the

pebble-smooth iphone with it’s crystal screen.

I recently downloaded an application written for iPhone.

The piece is by Aya Karpinska, a New York based poet,

artist, game designer and ‘designer of interactive

experiences’.

A simulation of the application can be found on the

website: http://technekai.com/

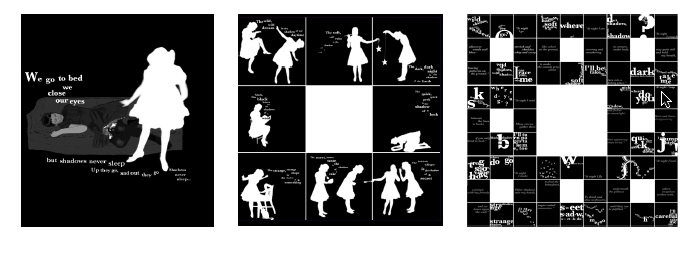

Aya calls her piece a ‘zoom narrative’ it is called

‘Shadows Never Sleep’ and makes use of the iPhone’s touch

screen to create a children’s story of images and words.

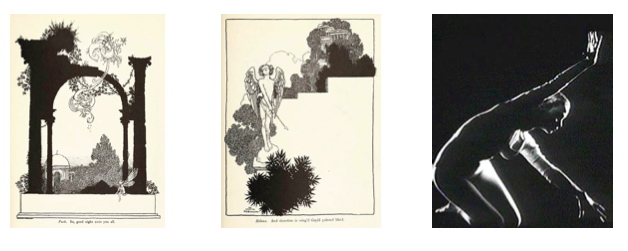

In essence it is a very simple piece. Based on photographs

of a woman, dressed in the short pleated skirt and puff

sleeves of a Red Riding Hood, an Alice or a Wendy. White

silhouettes against black. The photographs bring classic

illustrators to mind: W Heath Robinson’s illustrations of

Hans Christian Anderson, Shakespeare, and the Arabian

Nights, Florence Samson’s ‘Aesop’s Fables’, Rackham, Mucha

and Beardsley, I am reminded of animators as well: Lotte

Reiniger and Norman McLaren.

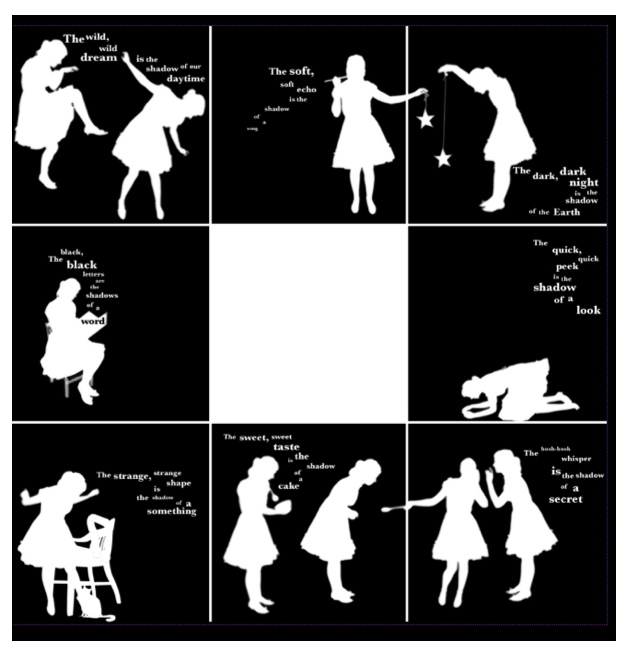

‘Shadows never sleep’ has

very minimal interaction, the viewer is presented with an

image of a girl asleep, and her silhouette or shadow rising

from the bed. Thus by implication the narrative that

follows is a dream sequence. By zooming in on this first

image the reader is taken to a set of nine squares with the

centre square blank, based on the ‘Sierpinski Carpet’ a

formula for a two dimensional tiled fractal. Further

zooming takes you to a second screen, where the pattern is

multiplied by itself to show a grid of nine by nine tiles.

To navigate this large image

the narrative make use of the iPhones ‘flick panning’: the

way in which moving a fingertip across the screen will

cause the image to move, with the automatic easing that

makes the image continue to flow across the screen until it

comes to a graceful stop; an interactive ‘Ken Burns’

effect.

I would like to create

something along the same lines, a piece that is somewhere

in that place between still image and movie, a combination

of images and text, a short sequence of images, some still,

some that imply some movement in time, some that animate

with a touch of a finger. I have been experimenting with a

flash/web based story book, the content produced by my

students, the pages turned with a drag of the mouse. The

story in text, with the book looking like a story book, but

the illustrations animated on the page.

And I am also fascinated by the concept of the silhouette

as an illustrative device, interested that silhouette

illustration has become so entwined with fairy story. There

is some intertwining here between the concept of shadow,

with it’s echoes of Jungian psychology, the dark side, the

hidden, the menacing, the ‘other,’ and the silhouette, as a

flattened pictorial device, different from the chiaroscuro

of the comic book and film noir, perhaps more akin to mime,

the aesthetic in the gesture, form, the detail in the

outline on a flat two dimensional surface, a cut-out.

Aya Karpinska also produced an image sequence called ‘From

the Balcony’ using a set of photographs by Ana Luisa

Figueredo, intended to be viewed in the photo browser of

the iPhone. Both of these works are intended as children’s

story. Aya’s starting point was an exploration of the

tradition of children’s literature. I plan to base my own

work around the possibility of collaboration with my

students We have been experimenting with silhouette

animation and with animations that ‘scrub’ on an ipod or

screen. This area between still frame, short sequence and

animation is a very rich area for exploration, especially

in the context of work aimed at a young audience.

As with ‘Shadows Never Sleep’, ‘From the Balcony’ is in

essence very simple, using the iPhone to replicate the page

by page structure of a traditional children’s book. The way

in which a movement of the finger on the screen will change

the image, like the turning of a page, and the built in

accelerometer moving the image seamlessly as the device is

tilted from portrait to landscape.

A narrative implies a

duration, a passage through time, a journey, an

exploration. Both of Aya Karpinska’s pieces have the feel

of the traditional book, with a beginning and an end. The

tactile nature of page turning replicated and replaced by

the touch sensitivity of the screen. In ‘Shadow’s Never

Sleep’ there is some limited choice as to the sequence in

which the text can be read, and by zooming out fully the

whole carpet of images and words can be seen at a glance.

It is this that I would like to explore.

Seeing a whole picture rather than glimpses seen scene by

scene on a time line.

My students creating a

shadow play - a retelling of Hansel and Gretel

In writing about database narrative in his book ‘The

Language of New Media’ Lev Manovich touches on the

difference between random access media and

sequential-access media, stating that a book can be either

or both - a story to be read from beginning to end, or a

dictionary of reference material to be dipped into at any

point:

“For centuries, a spatialized narrative in which all images

appear simultaneously dominated European visual culture; in

the twentieth century it was relegated to 'minor' cultural

forms such as comics or technical illustrations. 'Real'

culture of the twentieth century came to speak in linear

chains, aligning itself with the assembly line of the

industrial society”

Linear chains, chained to time, or patterns that can be

seen whole, but explored in detail. (perhaps this is the

difference between a labyrinth and a maze). The choice as

to how the detail is explored, the element of time, how

much time to give to the exploration, this is the choice of

the audience. And the audience also augment the narrative

with the knowledge and experience they bring with them.

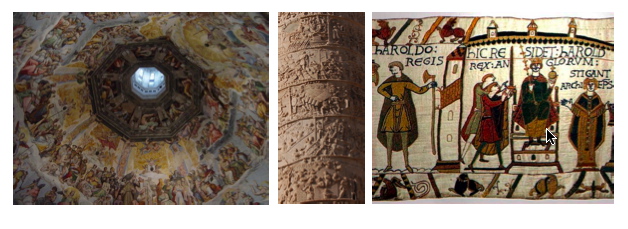

Having been immersed in the concept of the book from my

mother’s lap, it is impossible for me to imagine a life

without reading. In the summer I stood in the Duomo in

Florence, looking up at Brunelleschi’s extraordinary cupola

and the story of heaven and hell that the fresco painted on

it depicts. Towards the base of the fresco there are naked

figures in purgatory, chased by devils with flaming brands.

Towards the top figures of apostles leaning over a balcony.

The message is very clear - behave or be damned. This is a

cameo, or a series of glimpses that tell a story. And the

story would already have been well known to it’s intended

audience. Like Aya Karpinska’s ‘Shadow’s Never Sleep’ I can

see the story as a whole, or focus in on a single detail.

We may not know the specific detail, but we know the story,

we know the form, we know what to expect, we can read the

symbols. With a painting, We can see the story as a whole,

all at once, or zoom in on details within the bigger

picture, augmenting these with our own knowledge

understanding, making the connections. In the Duoma the

viewer has to climb the many steps to the upper gallery in

order to delight in details close up. But the climb is

rewarded by the chasm created by the extraordinary

perspective in the tiled floor far below, echoing the shape

of the lantern tower above. Brunelleschi has build the

story of heaven and hell into the very fabric of the

building. As media the Duoma is both immersive and

interactive.

Trajan's Column or the

Bayeux Tapestry are similar examples, as are the majority

of the National Galleries collection of paintings. Have we

lost an ability to read these stories to some extent, or is

it there still in a collective subconscious, deeply

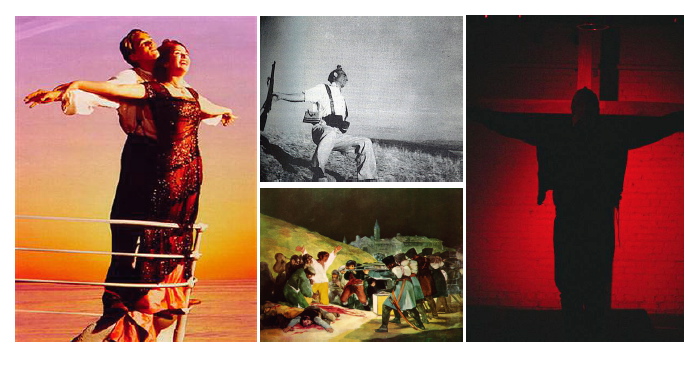

embedded? Rose on the prow of a virtual Titanic, holding

her arms wide, symbolically at a barrier that she may

cross, in the pose of Icarus, Christ; Capa’s Spanish

soldier, Goya’s peasant execution. A universal gesture

deeply ingrained in our visual culture.

That particular image from

‘Titanic’ captures the essence of the movie in a single

frame, the movie poster, the Tablaux Vivant.

Also in Florence I also stood in front of Titan’s ‘Venus

D’Urbino’. With tears in my eyes. Why should this painting

have this cathartic effect on me? Tears were also in my

eyes as I stood in front of a Rothko, recently, staring

into a frame of free colour floating above the surface of

the canvas. As an art student I have learned a language

with which to appreciate this work, a language that would

have Brunelleschi bemused I am sure. The still image is the

apex of Freytag’s triangle, the cathartic moment of

Aristotle’s ‘poetics’ with the other elements provided by

my learning and memory, the picture that I build in my head

that is based on my learning and memory.

It is impossible for me to imagine life without reading,

and impossible to imagine how it would be to look at image

without the knowledge of pictorial perspective. Having

learned the conventions of perspective as pioneered by

Brunelleschi it is not possible to see without this

knowledge, except perhaps through the eyes of a young

child. Equally I bring with me all my learning, both

individual and through the collective culture and time into

which I have been born. Similarly art must reflect the

culture and time in which it is created, the languages can

be developed, but not un-learned. Much of the art of the

first half of the 20th century was based on collage,

montage, mosaic. I was standing in front of a large pop art

collage at the Pallant House Gallery, a piece that can seen

as a whole, or read bit by bit, by connotation, by

association, by connection, by juxtaposition. And over the

same period artists such as Dziga Vertov with his clasin ‘

Man with a Movie Camera’ were developing the language of

the moving image:

“Montage aims to create visual, stylistic, semantic, and

emotional dissonance between different elements. In

contrast, compositing aims to blend them into a seamless

whole, a single gestalt.”

If this is in essence the language of film, what will be

the language of the new media? Manovich would argue that it

is database based. The database has become a very powerful

entity in many areas of contemporary society. He also

speaks of multiple frames, multiple windows creating a

‘spacial montage’:

“Time becomes spatialized, distributed over the surface of

the screen.”

Most films are story boarded as a part of the production

process. Time is represented in the gutters between the

images. One of the images in Aya Karpinska’s ‘Shadows Never

Sleep’ crosses from one frame to the next, breaking the

convention of the frame, altering the embedded conception

of the frame as framing time, similar perhaps to the way in

which Woody Allen will suddenly talk to camera in ‘Annie

Hall’; breaking the mimetic flow. of the narrative. A comic

book, as Manovich points out in the quote above, shares the

attributes of a collage with those of liner narrative. In

film the viewer is gradually given clues, fed a little at a

time. A film may not follow time, but the narrative itself

evolves over time. In Catch 22 for example, the first scene

is also the last, although in the first scene there is no

sound, and no knowledge as yet of the context of the

action. Through both film and book the audience is fed the

same scene repeatedly, but with a little more information

each time the scene is replayed.

In montage all the elements of the piece are seen at once.

Somewhere in between there are works such as Zbig

Rybczynski’s reciprocating animation ‘Tango’ and Bill

Viola’s ‘The Passions’. Perhaps the other way about in the

films of Peter Greenaway. A favourite of mine currently is

a flash based web ‘object’ called ‘Dominique’

which is simply the facial features of a young woman on a

white background. Movement of the mouse and clicking of the

mouse buttons makes the model blink, smile, pout, wrinkle

her nose. There is nothing more to the site than this.

As I have stated I am interested in exploring the space

between still image and moving image, sequences of images,

images combining with text, a story told through multiple

images, frames; the time frame and the picture frame, and

interactivity.

There is great potential for exploring this in relation to

the iPhone, with it’s ability to detect motion, sound, and

react to image via it’s built in camera.

A still frame from my students

animation ‘bob and bobbina’ - a retelling of Hansel and

Gretel

The story that Aya Karpinska

presents with ‘Shadows Never Sleep’ is very simple, and all

the more charming for this. Some of the images are not too

clear, and I am not clear if this is intentional or not.

Neither am I sure to what extent this piece will entertain

the younger child that it is perhaps aimed at. I suspect

that it is much more interesting currently as a curiosity

to the more typical owner of an iPhone, but as an

interactive story for children I can see huge potential in

this. To be able to navigate through a story, perhaps using

the iPhone’s motion detector to move around an image, like

a virtual ‘ball and maze game’, or to jump to another view

with a voice command, a click of the finger, or to zoom

back and forth through multiple images, each growing from

the previous. Perhaps using the camera to scan QR codes on

actual objects, to that the phone can participate in a

story based partly in the physical realm of books and

objects. I also enjoy the visual simplicity and complexity

of silhouette, and the anticipate the possibilities of

working with students, working with shadows and animation.